Estás usando un navegador obsoleto. No se pueden mostrar estos u otros sitios web correctamente.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

El Club del MiG-23/27 Flogger

- Tema iniciado Sflanker

- Fecha de inicio

Mig-23MF con numeral "17" en vuelo sobre Sovietskaya Gavan. La foto es de origen ruso así que no creo que sea una interceptación de un avión occidental sino más bien una práctica de vuelo en formación, ya que el avión va desarmado. Nótense los aerfrenos desplegados, la configuración del ala en flecha media y el morro alto para reducir velocidad. Foto de 1.978.

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar

ENCUENTROS EN LA GUERRA FRIA

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar/2008/04/encuentros-en-la-guerra-fria.html

Mig-23ML armado, volando con las alas en flecha mínima y los aerofrenos desplegados para mantener la formación con el avión que lo fotografía e intentar alejarlo de la zona. Aunque no tengo datos, la imagen quizas está tomada sobre el mar Báltico. Lugar de frecuentes encuentros durante la guerra fria.

Otra interceptación. Mig-23MF con numeral "27", armado y con tanques de combustible suplementarios bajo las alas, alabea para separarse del avión observador. Quizás esté lejos de su base y necesite el combustible extra. Sin datar, aunque probablemente más antigua que la anterior. Principios de los años 80 supongo. Los tanques obligan al Mig-23 a volar con sus alas en flecha mínima, aunque en caso de necesidad (combate) puede soltarlos.

ACTUALIZANDO

Gracias a diman val hemos podido solucionar el enigma del Mig-23UB de la entrada anterior. Para celebrarlo he realizado esta captura de imagen del avión en vuelo en un momento de la película.

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar/2015/09/actualizando.html

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar/2008/04/encuentros-en-la-guerra-fria.html

Mig-23ML armado, volando con las alas en flecha mínima y los aerofrenos desplegados para mantener la formación con el avión que lo fotografía e intentar alejarlo de la zona. Aunque no tengo datos, la imagen quizas está tomada sobre el mar Báltico. Lugar de frecuentes encuentros durante la guerra fria.

Otra interceptación. Mig-23MF con numeral "27", armado y con tanques de combustible suplementarios bajo las alas, alabea para separarse del avión observador. Quizás esté lejos de su base y necesite el combustible extra. Sin datar, aunque probablemente más antigua que la anterior. Principios de los años 80 supongo. Los tanques obligan al Mig-23 a volar con sus alas en flecha mínima, aunque en caso de necesidad (combate) puede soltarlos.

ACTUALIZANDO

Gracias a diman val hemos podido solucionar el enigma del Mig-23UB de la entrada anterior. Para celebrarlo he realizado esta captura de imagen del avión en vuelo en un momento de la película.

http://elhangardetj.blogspot.com.ar/2015/09/actualizando.html

Motocar

Colaborador

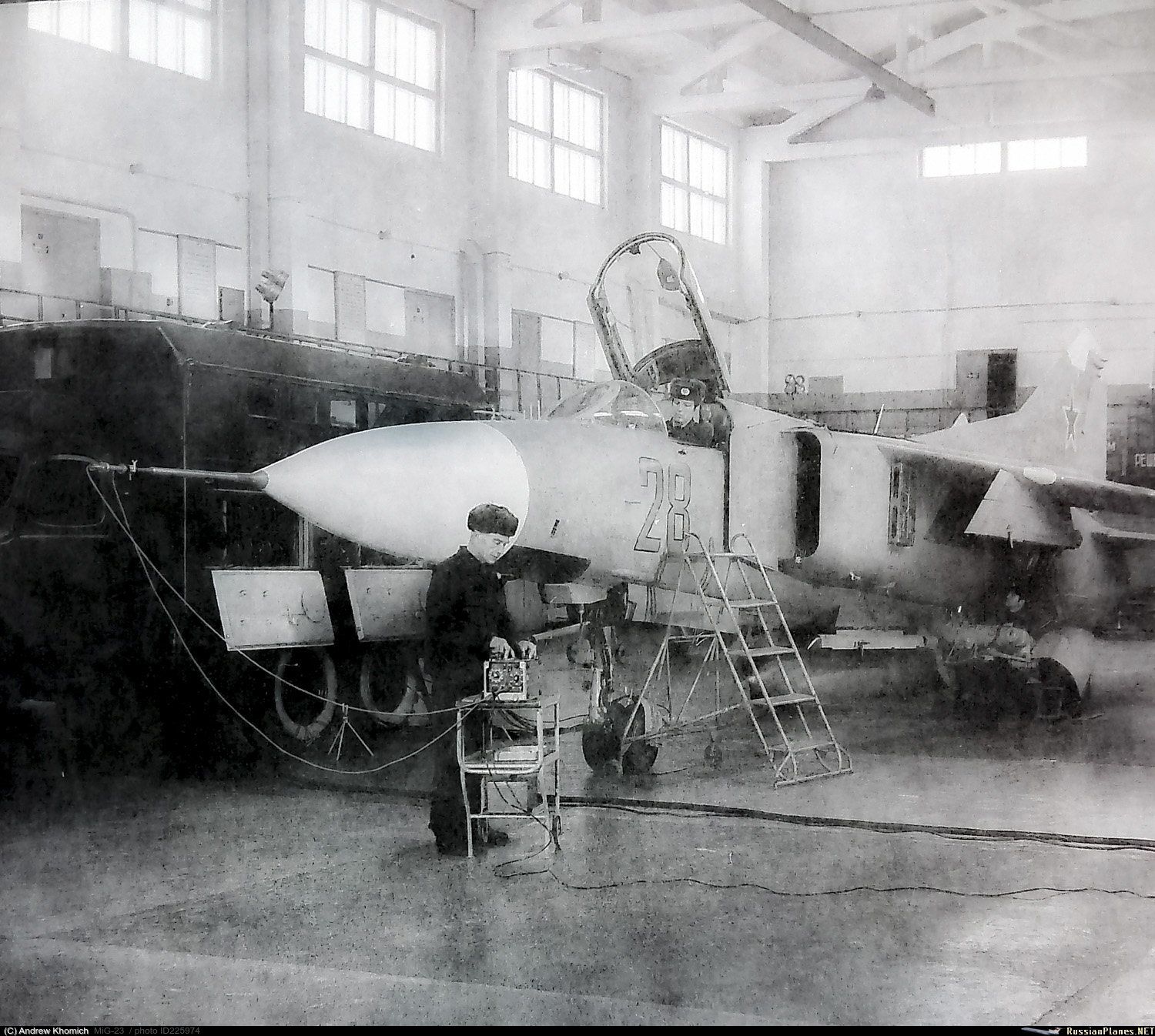

MiG-23 MLD, ultima actualización del MiG y compartido desde:

https://forums.eagle.ru/showthread.php?t=186423

MiG-23 sirio preparandose para el despegue

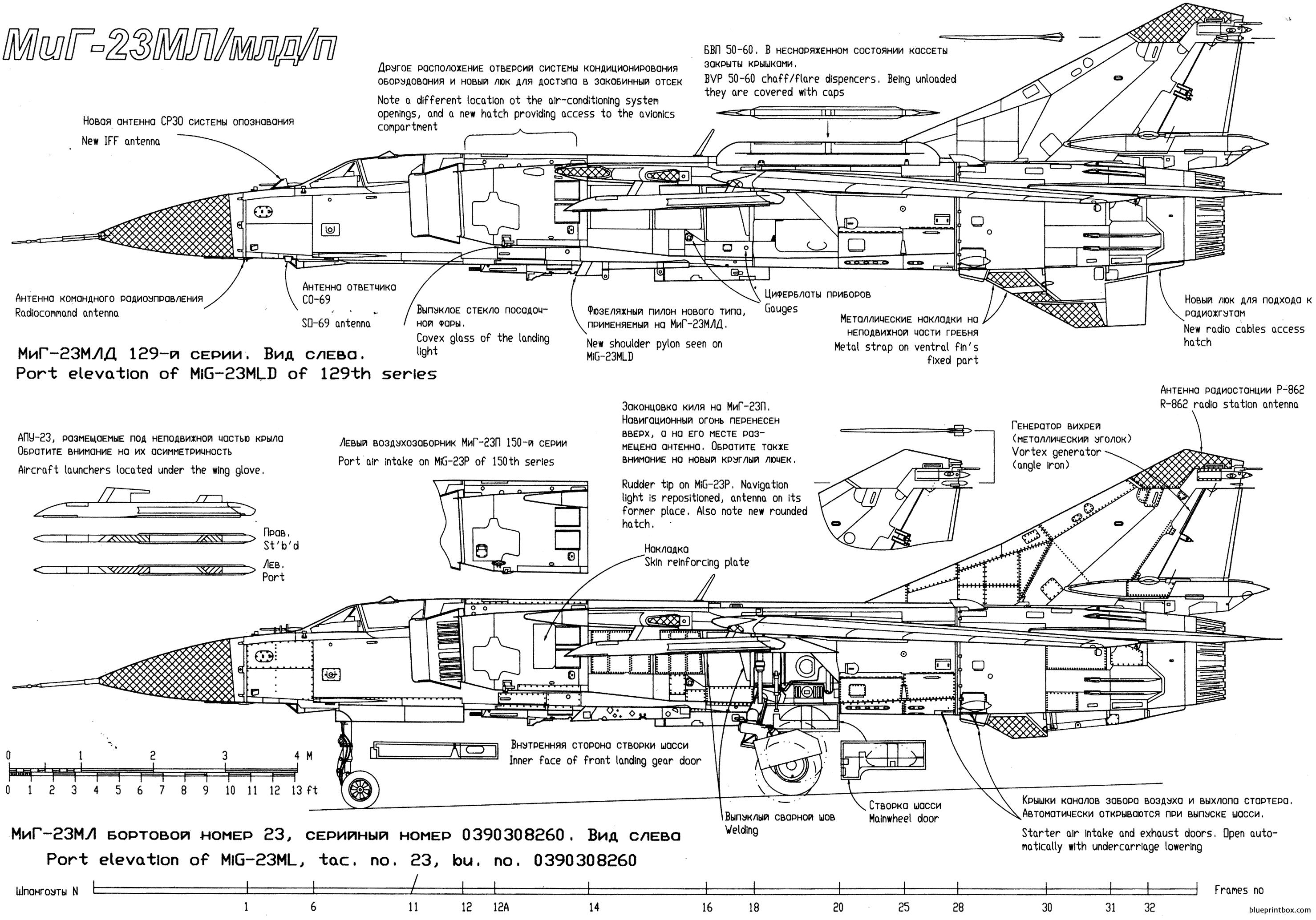

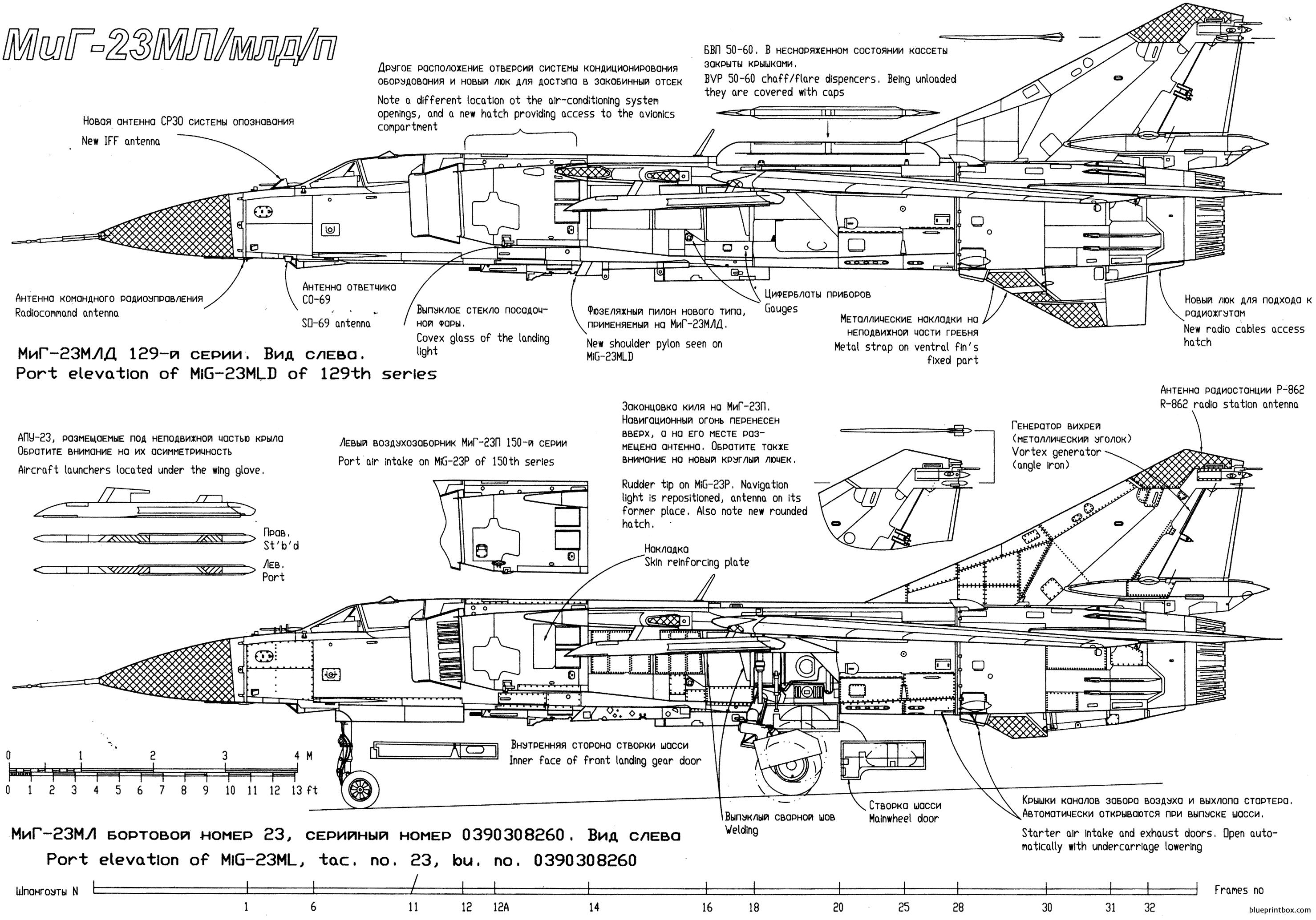

Perfiles MiG-23, compartido desde:

https://aerofred.com/details.php?image_id=87980

https://forums.eagle.ru/showthread.php?t=186423

MiG-23 sirio preparandose para el despegue

Perfiles MiG-23, compartido desde:

https://aerofred.com/details.php?image_id=87980

Última edición:

MiG-23UB Rumano

photo étonnante en pleine guerre froide ou est ce que je me trompe ?

1978 Entre Est et Ouest

Répondant à une visite de l’escadron de chasse 2/30 « Normandie-Niemen » en URSS, en juillet 1977, des Mikoyan-i-Gourevitch MiG 23 ML, arrivant de la base de Kubinka, se posent sur la base aérienne 112 « Marin la Meslée » de Reims, le 4 septembre 1978. Symbole des liens historiques qui unissent étroitement les deux forces aériennes, ces échanges n’ont pas cessé depuis lors.

@HernanF ,traducción por favor!

Gracias.

Foto sorprendente en plena guerra fría o es que me equivoco? [no, no te equivocás che]

1978 Entre el Este y el Oeste

Devolviendo una visita del escuadrón de caza 2/30 "Normandie-Niemen" a la URSS en julio de 1977, aviones Mikoyan-i-Gourevitch MiG 23 ML arriban desde la base de Kubinka y aterrizan en la base aérea 112 "Marin la Meslée" de Reims el 4 de septiembre de 1978. Símbolo de los lazos históricos que unen estrechamente a ambas fuerzas aéreas, estos intercambios no dejaron de suceder desde entonces.

De nada, CBU alias, mi nombre y apellido todo junto y en minúsculas

1978 Entre el Este y el Oeste

Devolviendo una visita del escuadrón de caza 2/30 "Normandie-Niemen" a la URSS en julio de 1977, aviones Mikoyan-i-Gourevitch MiG 23 ML arriban desde la base de Kubinka y aterrizan en la base aérea 112 "Marin la Meslée" de Reims el 4 de septiembre de 1978. Símbolo de los lazos históricos que unen estrechamente a ambas fuerzas aéreas, estos intercambios no dejaron de suceder desde entonces.

De nada, CBU alias, mi nombre y apellido todo junto y en minúsculas

Foto sorprendente en plena guerra fría o es que me equivoco? [no, no te equivocás che]

1978 Entre el Este y el Oeste

Devolviendo una visita del escuadrón de caza 2/30 "Normandie-Niemen" a la URSS en julio de 1977, aviones Mikoyan-i-Gourevitch MiG 23 ML arriban desde la base de Kubinka y aterrizan en la base aérea 112 "Marin la Meslée" de Reims el 4 de septiembre de 1978. Símbolo de los lazos históricos que unen estrechamente a ambas fuerzas aéreas, estos intercambios no dejaron de suceder desde entonces.

De nada, CBU alias, mi nombre y apellido todo junto y en minúsculas

Aguanta que ahí voy....

De esa visita salieron las fotos de mejor calidad del MiG-23 que ilustraron las publicaciones occidentales durante los 70 y 80, hasta la caída de la URSS

Temas similares

- Respuestas

- 25

- Visitas

- 2K